On Thumbs, or (Quitting Letterboxd)

Why the ratings system of two familiar critics stands tall amongst contemporary star espousal.

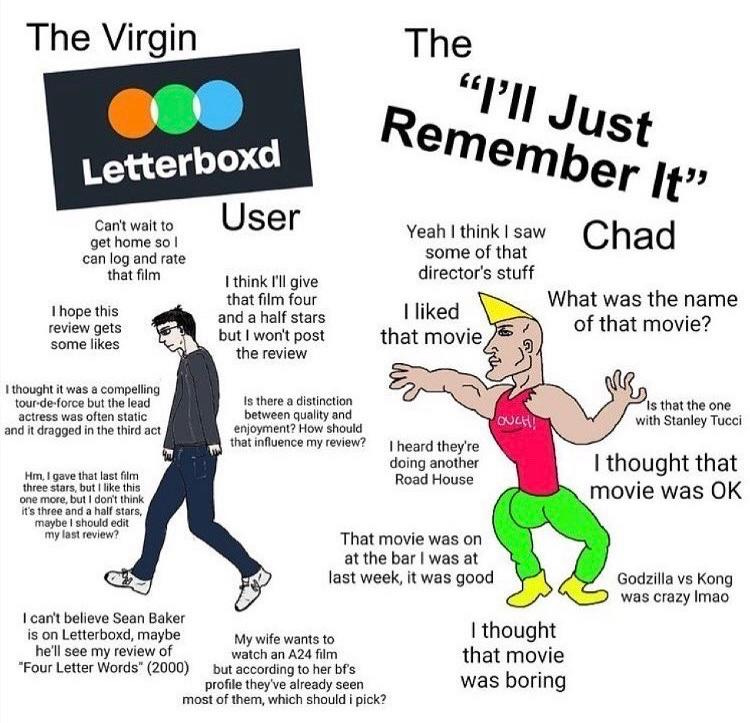

Imagine, if you will, the meme of the kid in school with veins popping out of his neck, clearly holding something back. That’s me, trying not to bring up the fact that I recently deleted my Letterboxd account. For a year or so, the malaise that came from using the app had become too hard to ignore, and I knew that it would soon be quitting time. I made an account on the site sometime in 2017, and since then, I logged every single film I saw, and I scoured the site for every film I had ever SEEN— to the best of my memory. For five of those 6 years, I also assigned a star rating to every film, and wrote a diary entry on roughly 70% of each new log. Seen as a tool for cinephiles, and a way to make friends online with fellow film-lovers, my view of the app as an oasis for my interest has fully shifted into a dead-eyed realization of its calamitous role in nudging the form that I love so much closer to death, and making an even worse name for film nerds.

First, let’s talk about what’s changed in the 8 years since I created my account. At the time, I don’t remember the stardom that you currently see amongst the site’s users. Accounts like Bratt Pitt (now, “gal pacino”), or Lucy’s certainly topped many of the public-review charts, but titans of mediocrity such as Karsten Runquist hadn’t built their brand on the site at that time, and have since used their platform to infect other platforms online. Quickly, a word on Karsten: I think that his popularity is as damning an inditement of the state of film culture (at least in my generation) as anything. The fact that he and his completely commonplace opinions on film can garner such a following, that he preposterously makes a career out of milquetoast “video essays”, or does numbers with some of the worst twitter-bait “joke” reviews on Letterboxd is completely sickening. My hatred of his can serve as a model for a person I believe should not exist— The film “personality” who cannot write or speak thoughtfully about films.

There are many incredibly smart Letterboxd users, some of whom are accredited writers whose work is published in genuine publications, and when I used the app I was often inspired by their words. When someone like Adam Nayman, Filipe Furtado or Sam Bodrojan would flick their fingers and string together a short and insightful response, there was potential for me to discover something new about myself and the film alike. When petulant twerps like the insufferable Reece (guywithamoviecamera) write their soy-ful reviews however, it is clear that they are in the business of clout, not thought. A word on Reece: I worked at a film festival last year and while I was on the clock he walked in with an identical-looking crony who was also dressed like a bisexual toddler. They were herded sloppily through the hallway, presumably to the next social checkpoint where they would slap their iPhone to a tripod and ask The Rock if pineapple belongs on pizza or whatever. I hate this type of person and I’m fairly sure they don’t really enjoy movies.

Getting back on track, I think that we have gone too far with the star rating system. I am a weak-willed individual but I think more people suffer from the star-poisoning that I caught from using Letterboxd than they let on. It usually goes something like this: three-quarters through the film you start pondering how many stars the film you are watching should earn—maybe it’s a 3.5? Does it do enough to be snag 4? You assign the film with 4 stars because you’ve heard that your parasocial besties really liked it, and you punch in some stupid fucking quip about how “James Cameron is mother” and shoot the review onto the web. After posting the diary entry, before the lights of the cinema come up, or you even process the film, you scan the opinions and values of those you follow.

David Ehrlich: 4.5 stars - “this work of high camp slayed the house down boots.”

Jay: 5 stars - “you vs. the Na’vi she told you not to worry about.”

Michael Mann Facts: 5 stars- “Dudes rock.”

Ok, the tastemakers have spoken- maybe it’s time to adjust those stars. You scale the review up to 4.5 stars, hopefully before any of your doting followers notice and think differently of you. While that demonstration is meant to service the general experience of rating films on the site, I did have my problems of viewing films through this quantifiable lens. This is all apart of the site’s plan to addict users into believing that their relationship with film must be performed at all times.

This is the problem with the “pics or it didn’t happen” nature of the site. A completionism mindset is necessary to garnering as much engagement as possible, therefore the act of watching films becomes a game, rather than the spiritual experience it should be. Many (including myself) will say they “need to see” such-and-such film, but do they ache to experience what they know is a great work, or do they need to have seen it—to equivocally and forever document the fact that they are knowing of a certain movie. Enter the growing passivity of the audience members engagement with the text. If the scope of one’s film expertise can be measured by their digital footprint, or their review—which consists of an amalgamation of smarter people’s opinions—then what separates watching a movie intently in the theater and giving it an honest shot at making an impression at you, and sliding the Criterion Channel tab to one side of your computer screen, while you surf The RealReal on the other?

Let me propose a different lifestyle: in the mid-70s film critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert began a long-running partnership as dueling film critics on various television programs. Described as “critic(s) for the common man” the pairing was an accessible place for viewers around the country to get an impression on the quality of whatever new films were being released on a given weekend. The program was founded on wit, the dynamic and arch relationship between the hosts, and a populist approach to film criticism. What I really like about the setup for the show, besides the earnest relationship the hosts had with film, was their rating system. If one of the critics liked a film, they would give it a thumbs up. If they didn’t like the film, a thumbs down. The system was easily digestible, and the combination of the two often dissenting opinions, i.e, “two thumbs up,” or “two thumbs down,” could give American viewers a sense of the general quality of a new release.

I admire the simplicity of the system, and I am going to reinstate it in order to communicate my thoughts from now on. Before any reader decries my willingness to bow to ANY system, and further commodify my relationship with movies, I would respond with a fact that any un-closeted cinephile will know intimately: if you are that friend who’s “into movies” you bear the responsibly of recommending or offering your opinions on films. When your aunt, significant other, or that person you can’t believe you’re still friends with asks how Poor Things was, you can use this system to simply describe your opinion: “One thumb up, one thumb down.”

Now, go forth, and please try to be less embarrassing about movies when you’re online!